Foreword

This is a paper that I have been preparing for a little while ; in the meantime, the French paper « Le monde » published this week end an excellent article on the mega constellations (link here, subscription required). As a matter of fact, I will try not to repeat what is in this paper, rather give my own opinion and some additional ideas or information that are not in this paper. Here we go!

Mega what?

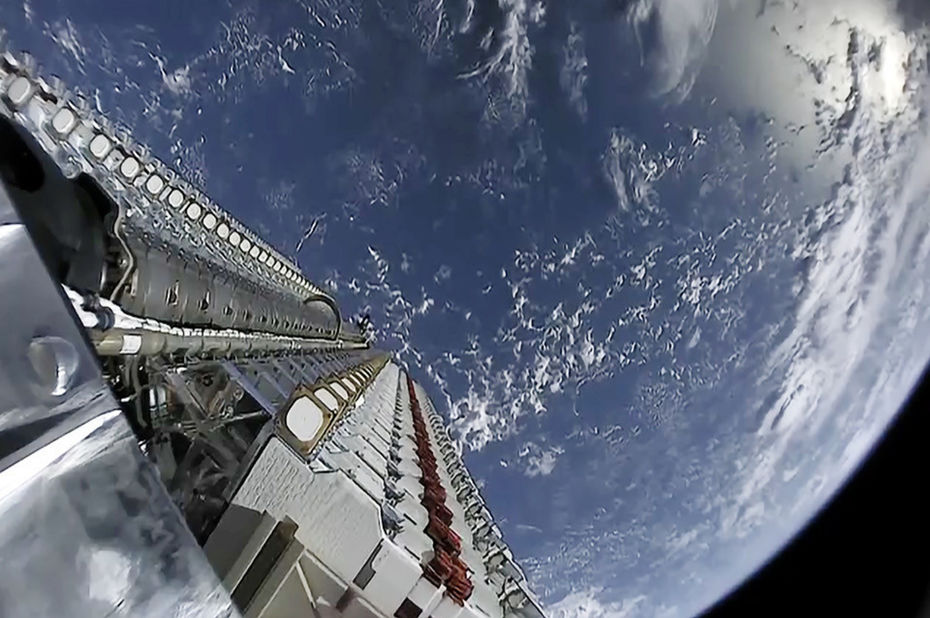

Yes, « mega constellation », a constellation of one million satellites? Maybe not, but still if you have a few hundred satellites in orbit, you can fall in that category…. I must stress that until recently (say 2020), the largest satellite constellation was an EO start-up, Planet Labs, with about 150 satellites in orbit. However, SpaceX caught up quickly with batches of 60 satellites at a time: it is right now the largest satellite system in orbit with more than 1300 satellites in orbit at early april ..

And many other projects are on the launch pad, with hundreds or thousands of satellites on the drawing board, to offer new services, mostly linked to connectivity. As a matter of fact, this concept is not new as it all started 30 years with the first generation of LEO projects: Teledesic backed by Bill Gates and cellular mogul Craig McCaw was the first such project with plans to launch up to 840 satellites already to provide broadband connectivity. Needless to say that this project never happened as NewSpace did not exist at that time… (Wikipedia article here)

A new century now and things have changed, satellites and launches costs have come down and people crave for connectivity all over the world: this may explain why there are in 2020 so many new projects in the works.

The incumbents

The following table lists the current incumbents of this mega constellation race. Curvanet and Guowang are the new players that just joined the pack.

| Project | Company | Size | Sats launched (03/21) | Frequency | Cost |

| Starlink | SpaceX (USA) | 12000 sats or maybe 42000 | 1300+ | Ku-Ka-V | 10B$++ |

| Kuiper | Amazon (USA) | 3236 sats | 0 | Ka | 10B$+ |

| Lightspeed | Telesat (CAN) | 298 sats | 0 | Ka | 5B$ |

| OneWEB | OneWEB (UK) | 650 sats | 180 | Ku | 5B$+ |

| Curvanet | Airspace Internet Exchange (USA) | 240 sats | 0 | ? | 500M$ |

| Guowang | CASC (China) | 12992 sats | 0 | Ka-V | ? |

| Hanwha | Hanwha (Korea) | 2000 sats | 0 | ? | 500M$ |

A few general comments when just looking at this table:

- Starlink leads the pack. Once again, Musk is doing a great job of execution: while he started after OneWEB, he has almost more than 10 times as many satellites flying and is already offering bete service. None of the other projects has launched anything yet (except PR). Who will catch up?

- So many satellites. The size of these projects is just amazing when you think that there are only around 4000 satellites in operations right now. This will probably create congestion in the LEO orbits and increase risks of collision. How about some international organization to regulate this?

- Big tickets. OneWEB with less than 1000 satellites was budgeted around 5B$ (as a reminder, this was approximately the cost of Iridium 25 years ago with only 66 satellites: thank you NewSpace!). Starlink with 20 times or 40 times more satellites is only twice as costly: the final tab will certainly be much higher! Will there be enough money for all these projects?

- Time to market. While Teledesic was too early, now might be the right time to market as in our modern societies, we cannot live without high speed connectivity. But only future will tell, right?

Main challenges

These projects all face the challenges of satellite telecommunication projects.

Challenge #1: get frequencies. This is often overlooked, but if you want to provide a connectivity service using radio emissions, you need frequencies. And when you plan to operate a global satellite network, you need these frequencies everywhere in the world unless you are ready to lose some markets. And if you want to do high speed broadband, you need a lot of MHz! Of course traditional satellite operators know this and they litterally sit on their own frequencies. Newcomers like the megaconstellation operators need to use frequencies that were not used: this is why all of them applied in Ku-Ka or V band: very high frequencies that took years to bring to maturity.

Challenge #2: finance it. Most satellite projects finish overbudget and mega constellations are risky as they cost billions with a great market uncertainty. As Musk said during the 2020 Washington DC satellite conference: “Guess how many LEO constellations didn’t go bankrupt? Zero ». Indeed a risky business so they are difficult to finance, as the chapter 11 filing of OneWEB demonstrated in 2020.

Challenge #3: build it and make it work. With money in the bank, the next challenge is to build the network and make it work. I must admit my admiration for these marvels of engineering and logistics. Mega constellations are a real change in scale: thousands of satellites to launch, continuous replenishment of the networks… Space really will turn into an industry, with high quality standards, as common as aviation…

However, for these projects, there is one key technology item that will drive their success: the user terminal. The frequencies used require electronically steered antennas that are complex to manufacture and are of a rather large size. The challenge will be to bring costs down (Starlink sells its beta antenna for 500$ and probably loses money) and to adapt it to mobility for new services. The antenna is the key for the quality of service and the success (or failure) of these ventures…

Challenge #4: make money. And here comes the fina l and most important challenge: will these projects succeed in making money? As a reminder, all the first constellations (Iridium, Orbcomm, Globalstar) filed for bankrupcy after their launch: their business model was flawed and they could not generate enough revenues…. Personally, I am doubtfull that a business model based on « the other 3 billions » without connectivity is a sound business. In addition, B2B markets like aviation, maritime and mobility are already addressed by existing operators. However, a business that targets white zones in rich countries has a potential, and it is what Starlink is doing with its beta program in NorthWest USA. They charge $100/month and beta testers seem to be happy. Starlink has an FCC licence for 1M stations and asked to go to 5M: if they can get that many users, this can bring more than 5B$/year in airtime. Musk said that Starlink would generate 30B$ in revenues, so there are certainly other markets to develop… And here is the key: speed and ramp-up. If you generate 30B$ in 10 years, it is too late, to repay your investors or your debt…

To finish on another note, there can be other strategic aspects to take into account. For example, Starlink is the #1 customer of SpaceX for its launches, so it is a way to bring launch costs down and to improve SpaceX’s already stellar competitivity. For Kuiper (Amazon), this maybe a perfect fit with AWS to connect the cloud evrywhere. And other projects, especially in China and probably OneWEB with Barthi’s investment, may have a sovereignty or power inclination… which leads to the conclusion of this paper on Europe..

And Europe?

Where is Europe in this race? At this stage, way behind, alas! After the OneWEB bankrupcy, early 2020, many European operators were approached to take over the company: all of them declined the offer in a great tradition of European risk aversion and skepticism… In summer 2020, the european commissioner Thierry Breton indicated that he was favorable for a European constellation. The European Commission passed a contract to 9 European space players (Airbus, Arianespace, OHB, Telespazio, TAS, Eutelsat, Hispasat, SES, Orange) to propose a scheme for such a constellation. The first feedback is expected in April… So there is a will at this stage, both political from the Commission, backed by financing and business from the operators which are seeing the threat and understand that they need to react.

At this stage, my final comments:

- At least the momentum has been created in Europe and history has shown (e.g. Galileo, Copernicus) that Europe can achieve great results in space

- While Starlink is up and running and the list of contenders keeps growing, let’s just hope that it’s not too late for Europe to have its own project. Or it will end up as an institutional program with no economic potential…

- None of the companies selected by the EC is a newspace company or an SME or a start-up: all the existing constellation projects are true disruptions from newcomers in space. The European project should take into account new ideas from people or companies outside of the traditional space/telco sector.

- Like for rockets (see my previous paper), Europe should not try to copy existing constellations but rather bring new ideas, both on the technology side and on use-cases

- And to conclude, while tax payer money is necessary for such projects, the private sector has also to take its share of the risks. The way it’s done in the US should inspire us: the government guarantees to buy services or products from the companies. This has worked to save Iridium and to kick start SpaceX while it leaves latitude to the companies to make their own choices. Food for thought!

Comments are closed